The Discipline of Writing and the Alphabet of Investing

Why writing is a part of our investment practice

One of the most overlooked skills in investing is not valuation, pattern recognition, or deal sourcing. It is writing.

Writing has a strange way of cutting through the noise in our own heads. You can think you understand a business model, an industry dynamic, or a management team. But when you try to put it into words, the gaps become obvious. Assumptions you had not noticed show up in black and white. A thesis that sounded compelling in casual conversation suddenly looks flimsy when typed out.

Writing forces the investor to crystallize an idea, to take something swirling in the abstract and make it concrete.

That act alone makes the process valuable, regardless of whether the conclusion is bullish, bearish, or inconclusive.

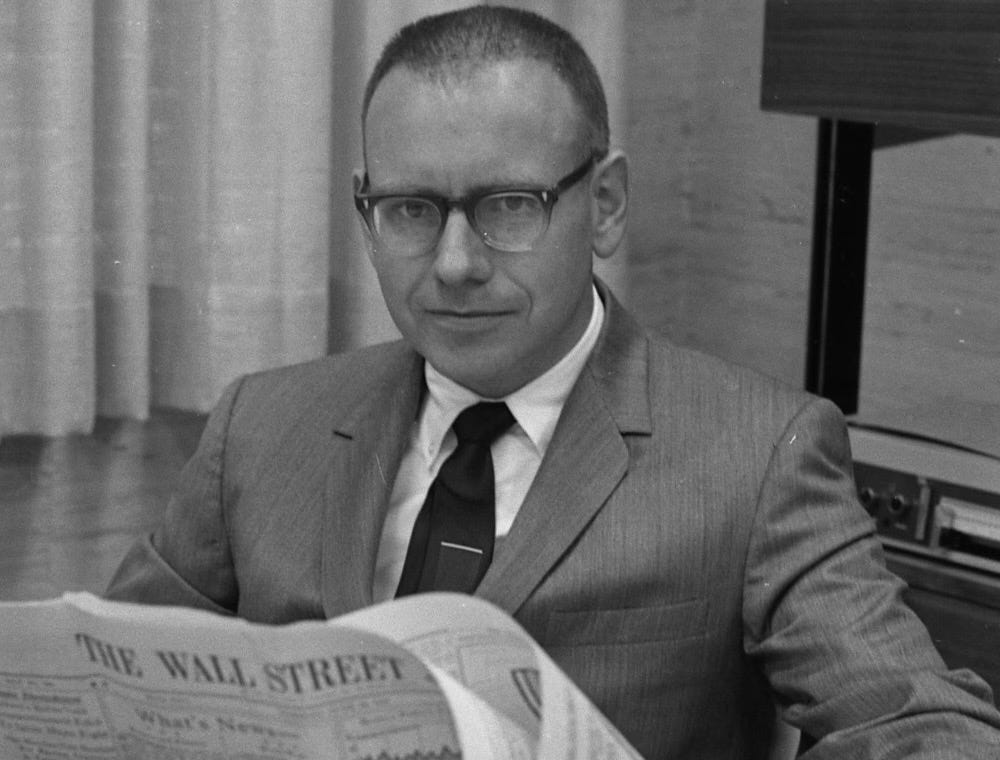

This insight is not new. Warren Buffett, in his early years, famously read through the Moody’s manuals line by line, company by company, starting with the “A’s” and working all the way to “Z.” There was no hack, no shortcut, no screen pulling the “best” 50 names. He did not know in advance which companies would matter. The only way to build true breadth was to grind through the universe methodically.

That approach was not about efficiency. It was about completeness. By seeing everything, Buffett built a map of the corporate landscape that few others possessed. He could connect dots across industries, spot patterns others missed, and call on a mental library when opportunities arose. His genius was not just in valuation. It was in the systematic accumulation of knowledge, brick by brick.

We have taken a similar approach in our own practice, with a particular focus on the neglected end of the market. Every day, we publish one or two notes on microcap companies we examine. This is not about producing content for its own sake. It is about charting the investable universe of sub–$500 million market cap businesses with the same systematic rigor that Buffett brought to the Moody’s manuals.

Microcaps present both the greatest opportunities and the greatest risks. They are underfollowed, underanalyzed, and often misunderstood. To navigate that terrain requires more than scanning for cheap multiples. It requires building a map of the landscape, cataloging the players, and creating a written record that sharpens judgment over time.

Each note we publish is a data point in that map. Taken individually, they are process artifacts. Taken together, they become a library of structured knowledge on a corner of the market that most investors ignore.

Markets do not reward half-baked conviction. They reward differentiated insight married to discipline. The act of writing sharpens both. It transforms fuzzy intuition into structured judgment. It also builds a personal record, a trail of what we thought, when we thought it, and why.

That archive becomes a powerful asset over time. A company we dismissed today might re-emerge two years from now with a different balance sheet, a new management team, or a fresh set of catalysts. Having that original note gives us an advantage. We can revisit our own reasoning, spot what has changed, and decide quickly whether the opportunity is different this time.

For us, the daily act of writing is a small but powerful way to make sure the process is real. It is not glamorous, but neither was Buffett leafing through Moody’s page after page. The point is to keep building the map of microcaps, one company, one note, one page at a time.